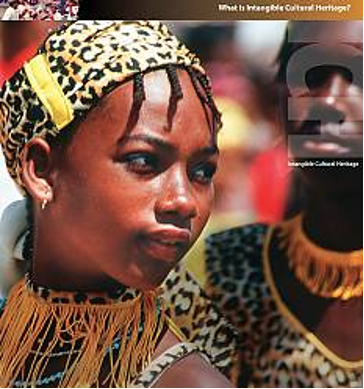

What is Intangible Cultural Heritage?

The term ‘cultural heritage’ has changed content considerably in recent decades, partially owing to the instruments developed by UNESCO. Cultural heritage does not end at monuments and collections of objects. It also includes traditions or living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants, such as oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe or the knowledge and skills to produce traditional crafts.

While fragile, intangible cultural heritage is an important factor in maintaining cultural diversity in the face of growing globalization. An understanding of the intangible cultural heritage of different communities helps with intercultural dialogue, and encourages mutual respect for other ways of life.

The importance of intangible cultural heritage is not the cultural manifestation itself but rather the wealth of knowledge and skills that is transmitted through it from one generation to the next. The social and economic value of this transmission of knowledge is relevant for minority groups and for mainstream social groups within a State, and is as important for developing States as for developed ones.

Intangible cultural heritage is:

Traditional, contemporary and living at the same time: intangible cultural heritage does not only represent inherited traditions from the past but also contemporary rural and urban practices in which diverse cultural groups take part;

Inclusive: we may share expressions of intangible cultural heritage that are similar to those practised by others. Whether they are from the neighbouring village, from a city on the opposite side of the world, or have been adapted by peoples who have migrated and settled in a different region, they all are intangible cultural heritage: they have been passed from one generation to another, have evolved in response to their environments and they contribute to giving us a sense of identity and continuity, providing a link from our past, through the present, and into our future. Intangible cultural heritage does not give rise to questions of whether or not certain practices are specific to a culture. It contributes to social cohesion, encouraging a sense of identity and responsibility which helps individuals to feel part of one or different communities and to feel part of society at large;

Representative: intangible cultural heritage is not merely valued as a cultural good, on a comparative basis, for its exclusivity or its exceptional value. It thrives on its basis in communities and depends on those whose knowledge of traditions, skills and customs are passed on to the rest of the community, from generation to generation, or to other communities;

Community-based: intangible cultural heritage can only be heritage when it is recognized as such by the communities, groups or individuals that create, maintain and transmit it – without their recognition, nobody else can decide for them that a given expression or practice is their heritage.

Intangible Heritage domains

UNESCO’s 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage proposes five broad ‘domains’ in which intangible cultural heritage is manifested:

Oral traditions and expressions, including language as a vehicle of the intangible cultural heritage;

Performing arts;

Social practices, rituals and festive events;

Knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe;

Traditional craftsmanship.

Instances of intangible cultural heritage are not limited to a single manifestation and many include elements from multiple domains. Take, for example, a shamanistic rite. This might involve traditional music and dance, prayers and songs, clothing and sacred items as well as ritual and ceremonial practices and an acute awareness and knowledge of the natural world. Similarly, festivals are complex expressions of intangible cultural heritage that include singing, dancing, theatre, feasting, oral tradition and storytelling, displays of craftsmanship, sports and other entertainments. The boundaries between domains are extremely fluid and often vary from community to community. It is difficult, if not impossible, to impose rigid categories externally. While one community might view their chanted verse as a form of ritual, another would interpret it as song. Similarly, what one community defines as ‘theatre’ might be interpreted as ‘dance’ in a different cultural context. There are also differences in scale and scope: one community might make minute distinctions between variations of expression while another group considers them all diverse parts of a single form.

While the Convention sets out a framework for identifying forms of intangible cultural heritage, the list of domains it provides is intended to be inclusive rather than exclusive; it is not necessarily meant to be ‘complete’. States may use a different system of domains. There is already a wide degree of variation, with some countries dividing up the manifestations of intangible cultural heritage differently, while others use broadly similar domains to those of the Convention with alternative names. They may add further domains or new sub-categories to existing domains. This may involve incorporating ‘sub-domains’ already in use in countries where intangible cultural heritage is recognized, including ‘traditional play and games’, ‘culinary traditions’, ‘animal husbandry’, ‘pilgrimage’ or ‘places of memory’.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the responsibilities of States that ratify the Convention?

At the national level, States Parties must: define and inventory intangible cultural heritage with the participation of the communities concerned; adopt policies and establish institutions to monitor and promote it; encourage research; and take other appropriate safeguarding measures, always with the full consent and participation of the communities concerned.

Six years after ratifying the Convention and every sixth year after that, each State Party must submit a report to the Committee about the measures it has taken to implement the Convention at the national level, in which they must report the current state of all elements present on their territory and inscribed on the Representative List.

States are also invited to propose elements to the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding and the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, as well as safeguarding programmes for the Register of Best Safeguarding Practices. States also have the possibility of asking for International Assistance from the Fund for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. The resources of this fund consist of contributions made by States Parties.

States Parties submit reports to the Committee on the status of elements inscribed on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding the fourth year following the year in which the element was inscribed, and every fourth year after that. States Parties beneficiaries of international assistance shall also submit a report on the use made of the assistance provided.

Such reports, including reports on measures taken to implement the Convention, are submitted to the eleventh session of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (see items 9.a, 9.b and 9.c of the Agenda).

Only States Parties to the Convention may submit nominations, but they have an obligation to ensure the widest possible participation of the communities in elaborating the nomination files and safeguarding measures. They must also obtain the free, prior and informed consent of these communities to submit a file. Nominations or requests for international assistance made by several States are strongly encouraged, as many elements of intangible cultural heritage are present in several territories and practised by a community established in several countries, contiguous or not.

What is the difference between the 1972 World Heritage Convention, the 2003 Convention for Intangible Cultural Heritage and the 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions?

The 1972 Convention deals with tangible heritage: monuments, as well as cultural and natural sites. Among other things, the heritage must be of outstanding universal value and of authentic character. Experts and site managers are key actors for identification and protection.

The 2005 Convention aims to provide artists, culture professionals, practitioners and citizens of the world with the possibility to create, produce, promote and enjoy a wide range of cultural goods, services and activities.

The 2003 Convention comes at the intersection of these conventions. Its aim is to safeguard a specific form of (intangible) heritage: practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, and skills that communities recognize as their cultural heritage. It is also a tool to support communities and practitioners in their contemporary cultural practices, whereas experts are associated only as mediators or facilitators. As a living form of heritage, the safeguarding measures for intangible cultural heritage aim, among other things, to ensure its continuing renewal and transmission to future generations.

What is the impact of inscription for communities and States?

The inscription of 429 elements has helped to bring attention to the significance of intangible cultural heritage thanks to the visibility it enjoys. A few years ago, the term ‘intangible cultural heritage’ was vague and mysterious, and sometimes derided. Media coverage at the time of inscription and beyond helps to popularize the concept and mobilize an increasing number of stakeholders, creating positive recognition of the fundamental importance of this form of heritage for social cohesion.

Once elements are included on the Lists, what steps does UNESCO take to safeguard them?

The safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage is the responsibility of States Parties to the Convention. Developing States have the possibility to request international assistance from the Intangible Cultural Heritage Fund. The grant is decided by the Committee (or its Bureau for amounts up to US$100,000).

There is also a process of on-going monitoring. Every four years, States Parties are required to submit a report to the Committee on the status of elements inscribed on the Urgent Safeguarding List, which must include an assessment of the actual state of the element, the impact of safeguarding plans and the participation of communities in the implementation of these plans. States Parties are also required to provide information on community institutions and organizations involved in the safeguarding efforts.

Furthermore, every six years, States Parties must present periodic reports on measures taken to implement the Convention, in which they must report the current state of all elements present on their territory and inscribed on the Representative List. These detailed reports contain information on the viability and action taken for safeguarding inscribed elements.

What are the risks and threats of inscription on the Lists?

There are threats and risks to intangible cultural heritage due to various types of inopportune activities. Heritage can be ‘blocked’ (loss of variation, creation of canonical versions and consequent loss of opportunities for creativity and change), decontextualized, its sense altered or simplified for foreigners, and its function and meaning for the communities concerned lost. This can also lead to the abuse of intangible cultural heritage or unjust benefit inappropriately obtained in the eyes of communities concerned by individual members of the community, the State, tour operators, researchers or other outside persons, as well as to the over-exploitation of natural resources, unsustainable tourism or the over-commercialization of intangible cultural heritage.

If an element is on the Representative List,does it mean that it is the best in comparison to other similar elements?

The inscription of an element does not mean it is the ‘best’ or ‘superior’ to another or that it has universal value but only that it has value for the community or individuals who are its practitioners. The element was proposed by a State that considers it ‘representative’ and is convinced that its inscription will allow a better understanding of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity and its significance in general.

Are languages in danger or religions eligible for inscription?

No. Specific languages cannot in themselves be nominated as elements to the Lists, but only as vehicles for the expression of the intangible heritage of a given group or community. A tradition requiring the use of a language (knowledge concerning nature, craftsmanship, performing arts) can be inscribed and its safeguarding will imply the safeguarding of the language concerned. The syntax, grammar and entire lexicon of a language are not considered as intangible cultural heritage under the terms of the Convention.

In a similar way, organized religions cannot be nominated specifically as elements for inscription, although a lot of intangible heritage has spiritual aspects. Intangible cultural heritage elements relating to religious traditions are normally presented as belonging under the domain of ‘knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe’ or ‘social practices, ritual and festive events’.

What happens in the case of controversial cultural practices, contrary to universal human rights?

As far as the Convention is concerned, it can take into consideration only intangible cultural heritage that is in line with existing international human rights instruments, as well as those that meet the requirements of mutual respect among communities, groups and individuals and of sustainable development. Controversial elements can still provoke fruitful discussions and encourage reflection on the meaning and value of intangible cultural heritage to communities, as well as its evolution and dynamic nature, which is constantly adapting to historical and social realities. At the national level, States can register what they consider appropriate for their inventories without intervention from UNESCO.